Freepaper “dictionary”

March 1995 ~ February 2000Moichi Kuwahara / Club King CEO, music compiler, producer

Text by SPREADFreepaper “dictionary”

Moichi Kuwahara (music compiler/CEO, Club King)

Began the “One Lunch Donation” through Freepaper dictionary (*1), contributed numerous reports for the publication, hosted the “Kobe ONELOVE” program on multi-lingual radio station “FMYY”.

We spoke with Mr. Moichi Kuwahara, who recognizes the importance of on-going media coverage, and has reported on the earthquake from a unique perspective in various forms over the course of 5 years.

Radio is imagination

After the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, I ultimately became involved in the radio show “Kobe ONELOVE”. I was most interested in the “imagination” aspect of the radio. When I was doing the “Snakeman Show” (*2) all I thought about was how I could get my audience to enjoy the show through the imagination. After Snakeman Show, I’ve continued to value the power of imagination in all areas of creativity.

It all began with the “One Lunch Donation”

I’ve never experienced war. I’d never thought about many people dying at once, or entire areas burned down. So when I first saw the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake being broadcast on T.V., I was in shock. It was during a meal, but I couldn’t continue eating, and was overcome with the chaotic impulse that I had to do something. “dictionary” was a bimonthly publication, both back then and now, so I was irritated by the lack of speed in the media to respond. So I thought that I should donate money, and thought about how I could do so, but never having done it before, I had no idea where to start. That was when I thought of the “One Lunch Donation” (*3), where people could give up one meal of their own in exchange for donating that cost. Perhaps people would be more responsive since after the 3.11 earthquake, but back then the response was slow. But in any case, I started with what I could.

Traveling with the donations

We have been publishing a “Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake Report” in dictionary, but one thing that was missing was the experience of actually traveling there. We had been receiving information through friends and acquaintances in Osaka, but somehow, we didn’t seem to be on the same page. We had sent donations a few times as well, but weren’t completely sure or aware of how things were going afterwards. I felt that if we continued in this ambiguous manner, dictionary would lose sight of itself, and decided to bring the donations there myself.

But when I got there, the first-hand accounts I heard were much different than the impression I had, and I was disillusioned. Their systemized way of processing donations did not move me at all. They call that year “the birth of volunteerism”, but we had no prior experience, nor knew of anyone who had done anything like that. We had misinterpreted the idea of “volunteering”. We thought that in order to help others, we had to live a life of altruism like Mother Teresa, and if we couldn’t go to that extreme, we shouldn’t bother. It felt as it that was the general mood surrounding us back then.

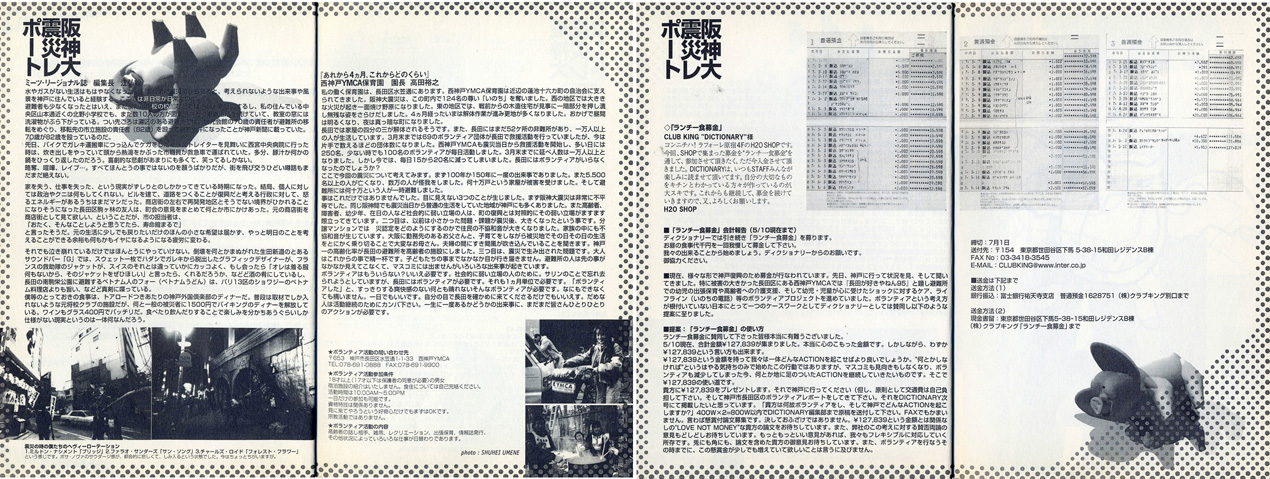

The circumstances leading to the founding of the radio show “Kobe ONELOVE”

The more I looked for where to make the donations, the more I was troubled. It was then that I met someone who informed me of community FM “FMYY”, a radio community operated by Father Kanda. “FMYY” was located in Nagata, in the city of Kobe. The community of Nagata was diverse, and the programming was done in 8 languages. I was first taken by surprise at that. I was shocked that there were at least 8 different nationalities living in that small area, and that the broadcast programming was done in 8 languages. When I heard what led to the founding of that radio station, I was deeply moved. The thing is, back then, the relief activities for victims were being carried out rather speedily. Food and water had reached far and wide, but relief to the people of those 8 nationalities was being put on the back burner. Under such circumstances, the network of Korean nationals in Japan took note of the situation, and created an emergency contact network in a 1 km radius from Osaka, which was as far as their radio waves could travel.

They began transmitting information such as when and where the next supply of water would arrive in their languages. I was touched by how the radio could provide a source of deep comfort by providing music in their own languages to those people who had been neglected in this dire situation. I was impressed by how the radio evokes our imaginations. My personal experiences in radio programming connected directly to this. Without thinking twice, I asked them to let me make a donation to them. They said they’d appreciate the donation, and asked me to also create a radio show. So we decided it would be called “Kobe ONELOVE”. That was how we began creating this new radio show.

A daily, two-hour show, from 6 p.m. ~ 8 p.m.

This excitement then continued to the founding of community FM in Shibuya, Tokyo. From there I spoke with clients who had been routinely supporting dictionary, and they readily agreed to support the founding of this new broadcasting office in Shibuya. Perhaps the atmosphere of the bubble economy was still wafting around back then. When we got started, we discovered that it was a lot of work to create a 3 hour program from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m., every day.

While “Kobe ONELOVE” was a community network, it grew to about 12 broadcasting offices at most. But community broadcast networks have no funding, so I’d go on field reports out of our own pockets, and first broadcast it on Shibuya FM, and send the program to other networks through cash-on-delivery. Field reports were conducted once every two months at most, and once every 3 months if I was busy. I usually interviewed 7~8 people, so the editing process required a lot of time. But since I was the one putting the content together…sometimes I’d select comedic songs like “Ora wa shinjimatta-da” (Hey, I died) after a really heavy story, so listeners probably didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. It was probably a pretty weird program. Even so, I think most people were crying as they tuned in.

I continued that for about two years, running on adrenaline, but it was difficult to create a program on a volunteer basis. I began getting complaints from the staff, saying “what are you doing when your own company isn’t even seeing profits?” so I couldn’t go on for long. I had been telling Shibuya FM from the beginning that they should create a disaster prevention focused program that reflects on what had happened because of the earthquake. Personally, listening to the experiences of the survivors of the earthquake and creating a show from that taught me so much. As it made us acutely ware of how small we are.

It’s not always a heartwarming story

The interviews were very colorful, to say the least. For example, there was one time that a woman, dressed in all black, who was about 190 cm tall, wearing super high-heels, suddenly came in for the interview. She had been a volleyball player, but suddenly made the decision to quit at the end of her high school years. But her mother had been training her since she was a small child to become a professional volleyball player. Despite that hard work, the daughter quit out of nowhere without talking to her mother, and for three years since that, they didn’t speak a word to each other. These two ended up getting shut in during the earthquake, and couldn’t leave or get help for days. Amidst this desperate situation, facing the possibility of death, they began to talk to each other little by little. They talked over everything they had kept locked up inside themselves?why she quit volleyball, why her mother couldn’t forgive her for it. They talked to each other to cheer up. Then they cried together and opened up and thawed their relationship that had frozen over. Because of the earthquake, they were able to become a real family. It was a story of loss and gain through the earthquake.

Then on the other hand, there were also stories of neighbors who were not on speaking terms, but helped each other out during the earthquake, and then after all that work recovering, went back to not speaking again. There were also other negative stories of robbery and violence as well. It has been 16 years (*4) since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, and while on the surface it seems that there was recovery, I don’t think it’s as easy for the heart to recover.

The things that go unsaid which should be valued

Many people were killed in the earthquake, and it filled the area with a negative energy, but through the interviews I was shown that there was just as much positive energy to be found. One time, a junior high age boy came as a volunteer. We tried to make him go back home, since he was just a child, but wouldn’t go home. We asked why, and it turns out he had no sense of belonging in the home. He had a family, but no real relationship with them, and felt he had no choice but to run away. His real family deserted him, but he found a new “family” through volunteering in Kobe. These children grew up with valuable experiences. They gained the know-how on volunteering, and can bring it back to their local community and put it into practice. In that sense, the earthquake did produce a kind of “positive” energy. These stories go untold, but I think they need to be recognized.

The people who have been excluded by society

Back then, outcasts and “shady” people came into our unordinary space by the hoards. There were those who did do bad things, and there were a lot of things to which nothing could be done, but among those outcasts, there were those that looked bad in appearance, but who actually came because they were lonely. These people would help the elderly with heavy things, and be thanked with tears, and feel accepted and recognized for the first time in their life. Even people with tattoos and other superficial attributes that usually frighten the elderly really showed that they weren’t scary on the inside. These elderly folks, some past their 70s, were all saying how wrong it was to judge people from their outward appearance. None of the volunteers I interviewed expressed that they were doing something for someone else. They all said “I did it for myself,” “I’ve never done something that became such a valuable experience for me like this in my life.” I think people are altruistic by nature.

There must have been other ways to do it

There was a huge difference between going there and conducting an interview myself, and writing an article based on a report given. In other words, one can only talk about something that one has experienced for oneself. We did create this radio show, and worked as hard as we could, but we still feel like we didn’t accomplish anything, and that there must have been other things we should have done, or other ways to have done them.

After311

Something we could finally do for the Great East Japan Earthquake was for our 140th issue (*5) of dictionary, for which Yoshitomo Nara’s artwork was the cover. An architect I trust had proposed the specifics for a temporary housing unit. All the proposals were realistic, so I hope that they will be utilized for future earthquakes. It’s a really tough time to find sponsors, so continuing dictionary will be a difficult task too.

I do want to say that going forward, instead of going by the conventional way of flattering corporations for their sponsorship, we must decide our own value for ourselves. Since 311, the government has declared that we ought to be responsible for ourselves, so I hope we can find ways to decide our own worth. It means that those who have only spent the money they earn on themselves can decide what is worth giving to, and support other people’s dreams or initiatives. To put it simply, let’s say that there is a CD being sold for \2,500. Whether that is a classic orchestra, or something someone made on their own, it is \2,500. That amount was probably put in place by the industry, but unfortunately, the value of the work was never defined. We had to be content with the value placed by someone other than oneself. To discern the value of a CD or performance on your own requires guts. Regardless of the money, if one can define the value of that music for oneself, then they can work hard for that value.

A portion of our hard earned money gets taken away in the form of taxes. Nobody ever challenged that, because it was understood to be the civic duty. But in an era where we define our own values, this should be taken into serious reconsideration. Corporations had directed our personal consumptions. And now we are confronted by the question: were we happy? We believe that since after311, the most important thing is not to stop thinking. Decide your own values. We have arrived in that kind of era. Defining the value of different things is all the same.

What to do now?

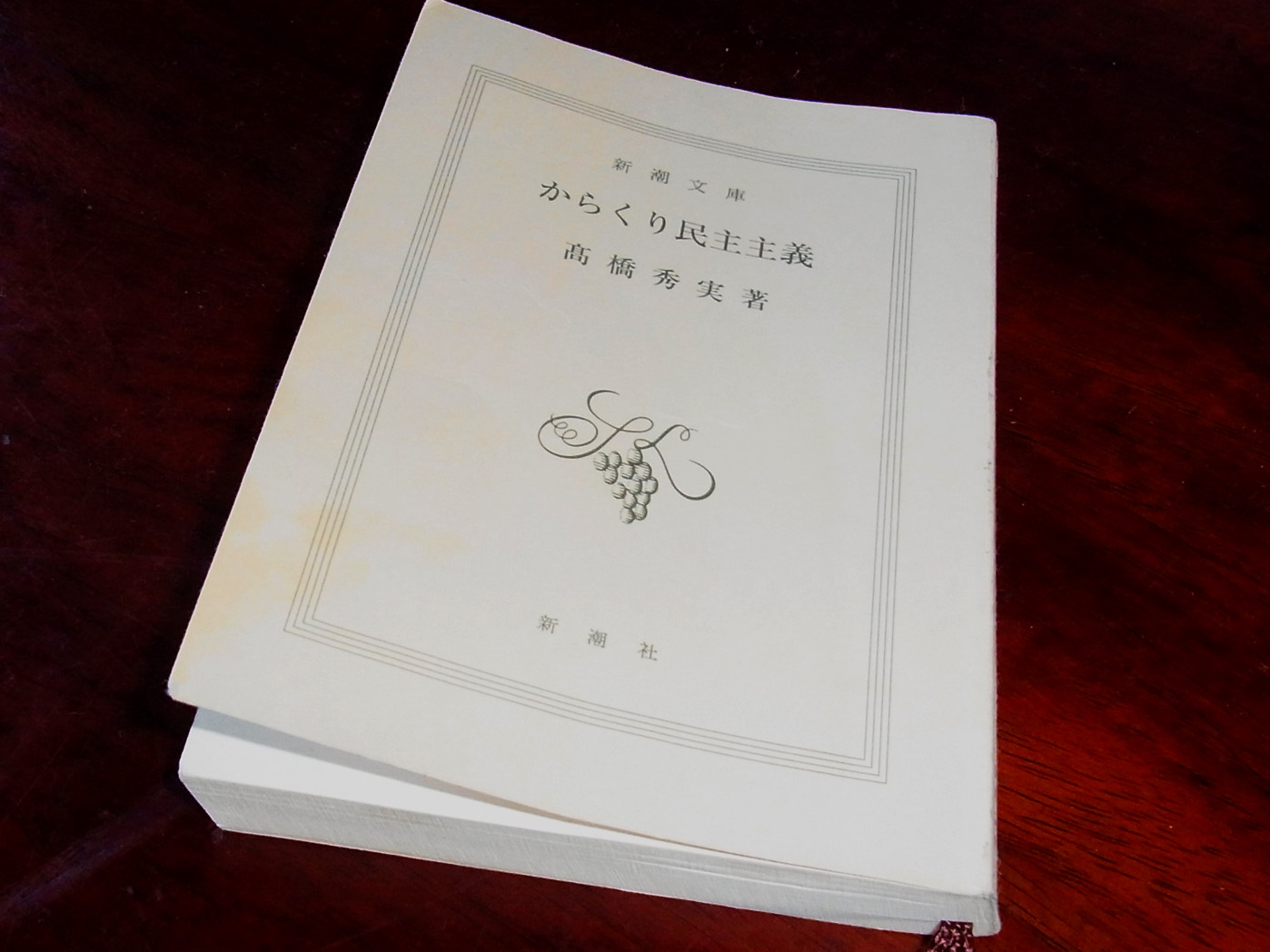

There is this amazing book. It’s called “Karakuri Minshu-shugi” (The Democracy Trick) by Hidemine Takahashi. At the end there is a commentary written by Haruki Murakami called “The Tricmampmampky World We Live In”, which is also great. Hidemine Takahashi is a writer who conducts a completely thorough research. He digs deep, trying to find the root of things. When you read this book, it becomes clear that the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, as well as the current Fukushima problem, are just troubling issues. This book, while saying “what do we do?” also investigates what is or was being done, and observes with a calm gaze, explaining the findings with a humorous air.

As we fully recognize that live in an era where we can’t go back to the way things were, I think those that will continue going forward, even letting go of everything they’ve gained, are the ones that are going to keep thinking, despite their concerns. It is a long process, and will challenge the very way we live.

(*1) The pioneer of “free newspapers” in Japan, established in 1989. It has provided a platform for a variety of artists and designers to present their work. http://dictionary.clubking.com

(*2) A legendary music radio show broadcast from 1976~1980.

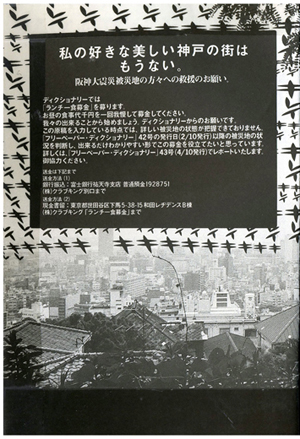

(*3) A charity initiative that began with the 42nd issue (March 1995) which was published right after the earthquake, asking people to donate \1,000 of their lunch budget.

(*4) Interview was documented in 2011.

(*5) Featured topic, After311 “Are Temporary Housing Units the Dream House of the Future?” Proposals by architects: Mineko Endo, Jiro Endo, Nobuo Araki, Satoru Ito.

Initial research

Date and time

14 times from Freepaper dictionary issue 043 (May 1995) until issue 057 (August 1997), about two years.

Background & Objectives

As the pioneer of Japanese free newspapers, “dictionary” (est. 1989) has provided a platform for artists and designers from a variety of genre to present their work. While producing the 42nd issue (March 1995) which was published right after the earthquake, it was still difficult to grasp the situation in the disaster zone, but they put a message on the cover saying, “We ask you to help the victims of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. Here at dictionary we are collecting a ‘One Lunch Donation’. Let’s start with what we can.” Since then, they published reports, donation statistic reports, and interviews that shared real stories in every issue. In April 1998, they began a radio show called “Kobe ONELOVE” which transmitted the content from dictionary to 11 networks in the country. Recognizing the value of continuous media diffusion, they reported Moichi Kuwahara’s unique perspective on the earthquake over the course of five years.

Target Audience

Survivors, and dictionary readership

Outline

“One Lunch Donation”, which called for donors to give up one lunch budget of \1,000 to donate. Wondering whether anything is being done while working from an objective position, Kuwahara decided to bring the money collected on his own to Kobe, where he donated it to “FMYY,” a multi-lingual radio station in Nagata. Then began an initiative to connect FMYY to the show that Kuwahara was producing at the time at Shibuya FM. Survivors and volunteers were interviewed, which was then edited and broadcast in both radio stations. People tuning in from the disaster-hit area were comforted by the songs they heard on the show.

Founder or organizer

Club King, led by Moichi Kuwahara (Music compiler, producer, CEO of Club King Co., Ltd.)

Location

Published in dictionary, SHIBUYA FM “VOICE” (Shibuya, Tokyo, 78.4MHz), FMYY (Nagata, Kobe, 77.8MHz), 9 other domestic radio stations.